iPhone pictures

The one camera I always have with me is my phone. I use it a lot and post many pictures to Facebook. It’s like taking notes. To me it’s the contemporary equivalent of an SX-70 but it’s even more fun to have an instant audience. Just like polaroids (and everything else), phone cameras have limitations. There’s nothing wrong with that. To do anything good with any camera you have to learn to see the way it does. Often, the cameras with the greatest limitations do the most interesting things, just ask Nancy Rexroth.

At some point soon, there will be a Facebook counterpart to this blog and that’s where they’ll go, but in the meantime here are two.

Minneapolis Institute of Art

I am lucky to live in Minneapolis for many reasons, one of which is the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Even if your benchmarks are the great museums of New York, Chicago, D.C. or Europe, MIA is a very good museum. Some areas are a little thin, 17th and 18th C European Painting, for instance, but then you get to the Rembrandt and all is forgiven.

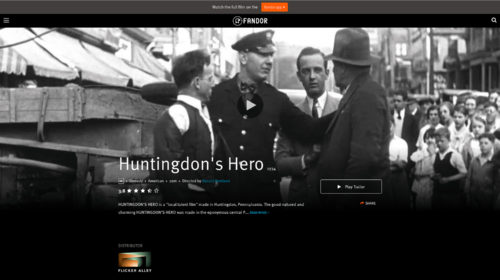

Huntingdon’s Hero

Huntingdon’s Hero, the orphan film made in Huntingdon, PA in 1934, is now on Fandor (available with a free trial). The only existing print of Huntingdon’s Hero was turned up by some of my students working on a short doc about the historic theater in Huntingdon. It had been missing since its last screening in 1969. It was a nitrate print, so highly flammable and dangerous (even just to have sitting around) so something had to be done. There’s a pretty long and crazy story about how that was all resolved, thanks to Bruce Davis at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. I wrote that story for The Moving Image, the journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists. Unfortunately, I can’t link to the full story but if you have access to MUSE you could find it, and there is an excerpt available here.

Johnny Gruelle

Since I brought him up in another post, I feel I should expand a little on Mr. Gruelle. Johnny Gruelle was a very accomplished illustrator up through the late 1920’s. He’s best known for creating and illustrating Raggedy Ann, although he did many other illustrations as well. His work is powerfully dark and strange. It made a deep impression on me as a child. He’s like the abandoned offspring of Maxfield Parrish and Diane Arbus.

If you only pay attention to the characters of Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy, they seem nearly the same as their modern incarnations. But while the modern illustrations are sunny, saccharine and open, Gruelle’s were childlike, beautiful, and grotesque – like dreams just before they go bad. And always that darkness behind everything, even the sunny, happy scenes.

My Gruelle books are all in storage, so I can’t scan the illustrations that made the strongest impression on me. Not surprisingly, the examples I can find online tend towards the sweeter ones. But there’s a witch in ‘The Lucky Pennies’, her face covered in … bandages? with those blank, steampunk goggles. She still gives me the creeps and she’s not the only one. The supporting cast of Gruelle is weird and dark, even the friendly ones.

Gruelle was also a casual racist, probably much of the reason his original illustrations have been largely forgotten. He had several characters: a maid named ‘Dinah’, ‘Beloved Belindy’ and ‘Little Black Sambo’ for which he shouldn’t be forgiven. I don’t remember those books well enough to comment on how those characters were presented in the stories but the illustrations speak loudly enough.

You don’t get to choose which images sink into your imagination as a child – some just swim right to the bottom and take up permanent residence without so much as a by-your-leave. Many books and things that I loved appear very different – and tainted – in retrospect: Raggedy Ann, Babar, Tintin, Gilbert & Sullivan, even Winnie-thePooh, but the images remain as powerful as ever.

Salon des Refuses

I’ve been invited to be part of a ‘Salon des Refuses’ here in Minneapolis, held for the large number of artists who were not chosen for the Wintertide show and others. Should be fun. This is the rejected picture that I’ll be putting in the show, the first of what I plan to be a series. It owes a lot to Johnny Gruelle:

This is a mixed media piece, on 11″ X 14″ Bristol Board. I prepare that by using tape to mark off both the borders and the white areas in the drawing, then use a mixture of acrylic raw umber and cheap gesso for the ground. The reason for the gesso is the ‘tooth’ it gives the surface – it works particularly well with pencil.

The show is the SweetArt Salon des Refusés Opening reception is Thursday, February 2, 2017 from 5:00 – 9:00 p.m.. The exhibit and sale runs through February 11, 2017. At the Northrup King Building.

Cubism, Picasso & Duchamp

The conventional wisdom about the ‘meaning’ of Analytical Cubism is that it’s an attempt to depict subjects from ‘multiple points of view’. You hear this all the time as received wisdom, from artists, students, teachers, critics and casual art enthusiasts. I don’t think so.

If Cubism is about the perception/depiction of space or an idea as pedestrian as ‘multiple points of view’, why is there not a single attempt at a 360 degree depiction – of anything? Analytical Cubism, as complicated as it may superficially appear, is stubbornly frontal. Why doesn’t Picasso ever talk about Cubism as an exploration of space? He never says a word about it. [Not that the words of artists matter that much. I care a lot more about what the work says than what the artist says.] Braque did once say that early Cubism was “the quest for space”, but that’s pretty vague. I’ll just say it: of the two of them, Picasso is the main driver of Cubism and – with a few exceptions – the better painter.

[An aside: How do you recognize a Pissaro in a room of Impressionists? By elimination. “Well it’s not a Morisot, not a Manet, not a Monet, it must be … ” The same is true of Braque. Sue me.]

There’s a reason why, as driven as Picasso is, there’s never any rigorous or methodical attempt to explore ‘space’. It’s that Cubism was never about ‘space’. Cubism is about the depiction of time, or more precisely, the experience of time.

There is a painting, often included in the Cubist canon, that really doesn’t belong there – it stands completely apart. Nude Descending A Staircase, by Duchamp, depicts a woman walking down a flight of stairs, very much like stop action photography would show it. It is carelessly labeled ‘Cubism’ without any appreciation for what it really is – a brilliant act of criticism and insight. Duchamp, one of the sharpest critics to ever wear the hat of an ‘artist’, is pointing out precisely what ‘Cubism’ really is, in its own language.

Cubism is the painting of time itself – the time it takes to make a painting, the changes in the subject over time or between sittings, in the painter and very importantly, the time it takes to read a painting. Being about time, it’s also about memory and the way memory functions. Many great Cubist paintings are like contained time loops which continuously bring a viewer back around to the beginning, like looped animations, or the nickelodeon loops popular at the time these paintings were made. Others may have noticed that when painted on rectangular supports, the corners of the pictures often fade into nothing – the meat of the painting is in an oval in the center. Picasso, particularly, came to paint many on oval supports or to draw Cubist compositions in ovals. I think there’s a connection between the circularity of the composition and the time loop it represents.

By necessity, Cubism is also about code – the radical abstraction and simplification of form needed to play with time. And that shared code, by extension, makes it a perfect vehicle for private jokes. Picasso does talk about that. He and his friends could read those paintings and get the jokes while those outside their group took the ‘signs’ to be purely formal. I don’t think this aspect can be stressed enough: Cubism is a game, played among friends.

Picasso is the Snorlax* in the road, as he said himself (in other words). To paint in any serious way you have to confront him. There’s no way around it. I could – and do – make the argument that most of painting since he died is less evidence of achievement than evidence of attempts to find a way around his body. But you can’t. And he’s not always great: the portrait of Vollard at the top of this page is staggering, but Ma Jolie, at the bottom, is pretty thin and mannered – practically a Klee (sorry, Paul). That doesn’t matter. It’s like Cezanne – no, he can’t paint a good nude with a gun to his head, but you have to face him where he’s best – and fail. That goes without saying.

*”Snorlax’s main role in the games [Pokemon] has been as a roadblock in the Kanto region.” Wikipedia.